VR is training cops to empathize with the people they might kill

- 06.17.19

- THE FUTURE OF POLICING

The company behind Taser weapons is putting Oculus Go headsets on Chicago police to train them in empathy—and teach them when to keep their weapons holstered.

It’s nighttime, and I’m on the front lawn, muttering to myself and pacing back and forth, something metal in hand. I’m yelling at the voices in my head and batting away my pleading mother when the police pull up. “Who sent you!” I shout at a cop. “Kyle, Kyle,” he says. “Put down the screwdriver, Kyle!”

Before the police can descend on me, everything fades to black, and seconds later, I’ve switched vantage points. Now I’m the cop, stepping out of the cruiser as the radio crackles with a report of a schizophrenic man off his meds. I see the guy talking to himself on the front lawn, and ask my partner to turn down the radio. As I approach Kyle, time slows down, and I am faced with a choice: engage in conversation or demand he drop the screwdriver and see where that goes.

It’s actually daytime, and I am in a glass-walled room in Seattle, wearing big headphones and an Oculus Go. Axon, the company that makes Taser weapons and body-worn cameras, invited me to their spaceship-like offices to share the newest piece of equipment they’re offering police agencies: Facebook’s virtual reality headset loaded with a pair of short, custom-made interactive films. The idea, Axon says, is to put officers in the shoes of someone experiencing an emotional crisis during a police encounter, and then let them practice how they might respond. The hope is, essentially, to train officers when not to use a Taser, or any weapon for that matter.

“Either in an arrest situation or just having a cop stop you and talk to you when you’re going through a psychotic episode can be very different from what the cops are expecting that person may be going through,” says Laura Brown, the company’s senior director of training strategy.The country’s steady decline in public funding for mental health services has made police the de facto first responders to people experiencing emotional crises, and those encounters are disproportionately likely to turn fatal: a 2016 report from the Ruderman Family Foundation found that almost half of the people who die at the hands of police have some kind of disability. A more recent study of unofficial databases built by the Washington Post and the Guardianfound that black men were the demographic most at risk of being killed during interactions with police, but people with mental illness across all groups faced a risk of death that was seven times greater than for those without.

“Verbal commands probably aren’t gonna work” in many of these situations, says Brown. “So how do we train de-escalation when the conditions aren’t going the way that we anticipate them to go?”

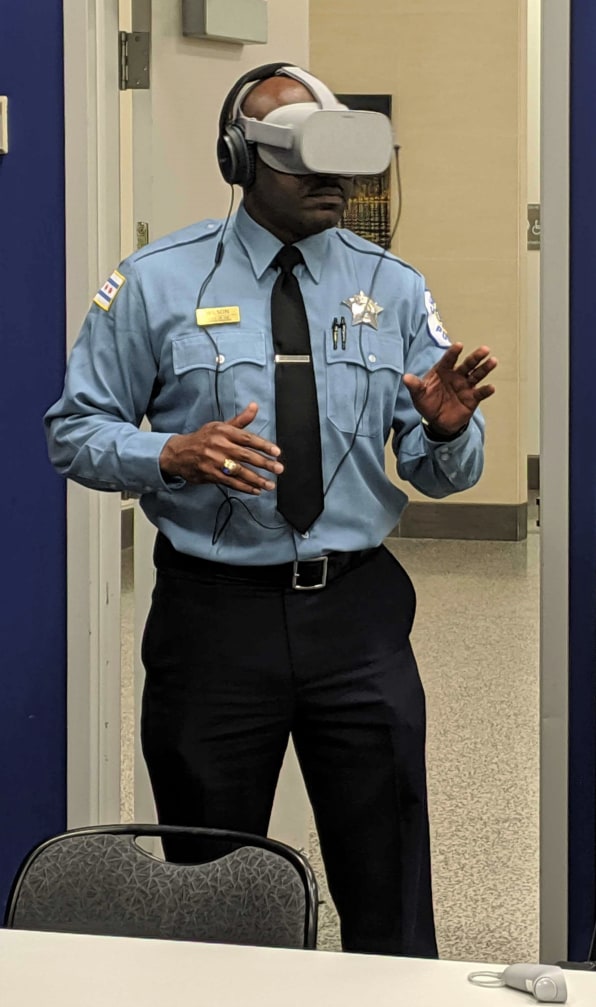

Axon, formerly known as Taser, produced the films last year in collaboration with mental health, community, and policing experts and rolled them out last month with a press conference at the Chicago Police Department, which will use a dozen helmets to train its officers. As part of ongoing efforts to improve its response to people in emotional crisis, the department has already put 2,700 officers through a 40-hour crisis intervention training course, or CIT, by the end of 2018.

“But they’re not really always available to go with you at that time,” says officer Roberto Garduno in a phone call. “Either they’re tied up with something else or they’re being assigned to a different job.” And Garduno and his colleagues are often encountering people in emotional crisis. “So we’re getting to the scene and we’re going with what we know.”

Public outrage in Chicago erupted in 2015 following the killing of Laquan McDonald, who was shot by a police officer 16 times. That year, the city also released video that showed that a 38-year old University of Chicago graduate student named Philip Coleman died after being repeatedly tased by Chicago police while in his jail cell.

His father Percy, a career law enforcement officer in the city, told the Chicago Tribune that the police knew that his son needed psychiatric help, which is why Coleman’s mother had called police on her son in the first place. “She didn’t call Chicago police to kill her son,” he said. “She called them for some help.”

Chicago later settled a $4.9 million lawsuit over Coleman’s death and has added new de-escalation training with a focus on encounters involving people with mental illness. Earlier this year, it negotiated a consent decree with the Dept. of Justice to enact further reforms.

There are no nationally uniform policies on Taser use—or on police practices in general—but the company’s training program has put a new emphasis on preparing for encounters with people in crisis. Axon is responding to changes that are sweeping across policing, changes that its own body cameras are helping to propel, Brown says.

“There’s been a demand for us to think a bit more about this from law enforcement, but I think that community message is resonating a lot more in the past couple of years, especially when we’re seeing this huge proliferation of body-worn evidence for all these different situations,” she says. “And it can be kind of a PR nightmare.”

It’s a recurring one for Axon. The company says hundreds of thousands of lives have been saved because of Tasers, which it has touted as a “less-than lethal” weapon since widespread adoption began a decade ago. But the weapons have also been implicated in numerous injuries and deaths, and people suffering from an emotional crisis may be at higher risk during Taser shootings. Tasers have also escalated some situations when they haven’t been effective at subduing an individual, as a web search for “taser failed” reveals and as reporting by American Public Media Reports has documented. In some of those situations, the suspect became more aggressive after a Taser was deployed, and was shot and killed by police.

Axon says it is continually upgrading the device, and contends that most of the deaths linked with its weapons have been a result of a person’s drug use, underlying physiological conditions, or other police force used along with the Taser. The weapon is “the most safe and effective less-lethal use of force tool available to law enforcement,” it says.

The controversies nonetheless helped set the stage for a transformation at the company. In 2017, it changed its name from Taser and began to pivot into tech company territory, touting new products like live-streaming body cameras and a cloud platform that will eventually bring AI tools to police video analysis.

POLICING ENTERS VR, WITH UNKNOWN EFFECTS

In a second VR film produced by Axon, I’m another young white man in crisis—this time affected by autism, not schizophrenia—and I find myself lost and confused in a mall parking lot. When I switch into the perspective of the responding officer, I again choose how to react by making eye contact with a series of text cards on screen: ask the man to talk, look for his parents, surround him. The options don’t include explicit use of force, like firing a Taser, but some choices are meant to escalate the situation.

Axon says the VR training is the first of its kind aimed at teaching police empathy. Officer Garduno, who had never tried VR before, said that inhabiting the point of view of the autistic man helped reinforce some of his deescalation training. “We’ve heard that loud sounds bother persons with autism, and that can change what happens,” he says.

While virtual reality has been widely touted as “an empathy machine,”evidence of the technology’s ability to actually instill empathy or sympathy remains minimal. A two-month study published last year by researchers at Stanford that gauged individuals’ feelings toward the homeless found some support for the theory. But the researchers also warned that not all empathy exercises produce positive effects. Previous studies have shown that when individuals are asked to take the perspective of their competitors, they can become less empathetic toward them. Others caution that VR-based empathy training can backfire if a participant concludes that another person’s situation is not so bad after all. Some police officers who have not used the VR training told me they were skeptical that empathy can really be taught at all.

Sergeant Kristofer Jenny of the Napa Police Department, who tried the first film at an Axon training camp last year in California, said the sensory immersion and perspective-taking had left an impact on him. “As someone who lacks empathy, I really had a different feeling of being in the perspective of a schizophrenic person,” he says.

In 2012, a Napa police officer shot and killed a 60-year-old man in front of his house while he was having a mental health crisis. Alongside crisis training and other reforms Napa adapted after the shooting, VR empathy training could help prepare officers for scenarios like that, Jenny says. “It provides a more human dimension to the decision making when it comes to, is this person a threat or not a threat? That’s important.”

The cost of the Oculus Go is also appealing, he says: $599 as part of the Oculus for Business subscription program (it retails for about $250). That makes VR training appealing for small, cash-strapped departments like his, especially when compared with other simulation options.

Police have relied on non-immersive video training and role-playing scenarios for decades, including some trainings aimed at helping officers hear what a person with a mental illness may be seeing and hearing. The US military uses VR for tactical training and to help soldiers and veterans cope with traumatic experiences, and some of these applications are filtering down to local police agencies. In April, the New York Police Department participated in a room-scale video-game-style VR training designed by V-Armed, which placed officers in an active shooter scenario at the World Trade Center Memorial and a hostage situation in a public school.

The NYPD is also using VR in its community outreach efforts. The Police Foundation has invested nearly half a million dollars into a simulation aimed at training high school-age teens in New York how to avoid gangs. In one of the scenarios, developed with Brooklyn teens, a character describes a party that might involve drugs and sex: “We ain’t going to waste any time, we are out right now. You coming?” In another mode, teens can see certain scenarios through the eyes of a police officer.

VR is also being used to prepare nonpolice communities for encounters with law enforcement. An ongoing study in Philadelphia is examining the effectiveness of a simulation designed to help people with autism practice interacting with police and develop skills for improving those encounters. “Although many parents try to prepare their children for police interaction, immersive VR offers a novel opportunity to practice skills repeatedly, in a variety of environments and police contexts,” like keeping one’s hands in sight and speaking clearly, says Julia Parish-Morris, a research assistant professor at the Center for Autism Research at Children’s Hospital of Philadelphia and the study’s author.

Axon’s police training looks promising, says Parish-Morris, who suggests that the technology could help police prepare for encounters with other vulnerable communities. “Addressing the inevitable interaction between disability status and other factors such as race and gender is a very important next step toward true effectiveness,” she says.

Axon intends to assemble a crisis intervention training advisory board to guide the development of future empathy training scenarios. (Last year, the company convened an ethics panel to guide its use of technologies like face recognition, but a member of that group said that it had not been apprised of the VR training.) The company says it would also like to personalize the VR films and provide more real-time feedback to officers.

Related: Body camera maker will let cops live-stream their encounters

It may be more challenging to measure the impact that the VR actually has on enhancing empathy. Officer Garduno still sees the need to try.

“We have to make decisions all the time on the street in a split second,” he says. “The good thing about this kind of training is, if you do make the wrong decision, you can learn from your mistakes. If you make the wrong decision on the street, that’s it.”

If you are in emotional crisis or supporting someone in crisis, consider reaching out to a helpline. Call the National Suicide Prevention Lifeline at (800) 273-8255 or contact the National Crisis Text Line by texting “Hopeline” to 741-741. The National Alliance on Mental Illness offers suggestions on how to help someone in crisis.