The Truth About Customer Experience

Companies have long emphasized touch points—the many critical moments when customers interact with the organization and its offerings on their way to purchase and after. But the narrow focus on maximizing satisfaction at those moments can create a distorted picture, suggesting that customers are happier with the company than they actually are. It also diverts attention from the bigger—and more important—picture: the customer’s end-to-end journey.

Think about a routine service event—say, a product query—from the point of view of both the company and the customer. The company may receive millions of phone calls about the product and must handle each one well. But if asked about the experience months after the fact, a customer would never describe such a call as simply a “product question.” Understanding the context of a call is key. A customer might have been trying to ensure uninterrupted service after moving, make sense of the renewal options at the end of a contract, or fix a nagging technical problem. A company that manages complete journeys would not only do its best with the individual transaction but also seek to understand the broader reasons for the call, address the root causes, and create feedback loops to continuously improve interactions upstream and downstream from the call.

In our research and consulting on customer journeys, we’ve found that organizations able to skillfully manage the entire experience reap enormous rewards: enhanced customer satisfaction, reduced churn, increased revenue, and greater employee satisfaction. They also discover more-effective ways to collaborate across functions and levels, a process that delivers gains throughout the company.

Consider a leading pay TV provider we worked with. Although it was among the best in the industry at managing churn, it faced a maturing market, heightened competition, and escalating costs to keep its best customers. Churn was a familiar problem, of course, and the typical reasons for it were well understood: Pricing spurred some customers to leave, while competitors’ technology or product bundles lured others away. The common ways to keep customers were also well known, but they were expensive, including such things as upgrade offers, discounted rate plans, and “save desks” to intercept defectors. So the executives looked to another lever—customer experience—to see if improvements there could reduce churn and build competitive advantage.

As they dug in, they discovered that the firm’s emphasis on perfecting touchpoints wasn’t enough. The company had long been disciplined about measuring customers’ satisfaction with each transaction involving the call centers, field services, and the website, and scores were consistently high. But focus groups revealed that many customers were unhappy with their overall interaction. Looking solely at individual transactions made it hard for the firm to identify where to direct improvement efforts, and the high levels of satisfaction on specific metrics made it hard to motivate employees to change.

As company leaders dug further, they uncovered the root of the problem. Most customers weren’t fed up with any one phone call, field visit, or other interaction—in fact, they didn’t much care about those singular touchpoints. What reduced satisfaction was something few companies manage—cumulative experiences across multiple touchpoints and in multiple channels over time.

Take new-customer onboarding, a journey that typically spans about three months and involves six or so phone calls, a home visit from a technician, and numerous web and mail exchanges. Each interaction with this provider had a high likelihood of going well. But in key customer segments, average satisfaction fell almost 40% over the course of the journey. It wasn’t the touchpoints that needed to be improved—it was the onboarding process as a whole. Most service encounters were positive in a narrow sense—employees resolved the issues at hand—but the underlying problems were avoidable, the fundamental causes went unaddressed, and the cumulative effect on the customer was decidedly negative.

Remedying matters would add significant value, but it wouldn’t be easy: The company needed a whole new way of managing its service operations in order to reinvent the customer journeys that mattered most.

More Touchpoints, More Complexity

The problem the pay TV provider encountered is far more common than most organizations care to admit, and it can be difficult to spot. At the heart of the challenge is the siloed nature of service delivery and the insular cultures that flourish inside the functional groups that design and deliver service. These groups shape how the company interacts with customers. But even as they work hard to optimize their contributions to the customer experience, they often lose sight of what customers want.

The pay TV company’s salespeople, for example, were focused on closing new sales and helping the customer choose from a dense menu of technology and programming options—but they had very little visibility into what happened after they hung up the phone, other than whether or not the customer went through with the installation. Confusion about promotions and questions about the installation process, hardware options, and channel lineups often caused dissatisfaction later in the process and drove queries to the call centers, but sales agents seldom got the feedback that could have helped them adjust their initial approach.

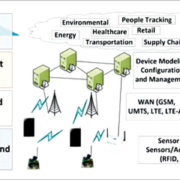

The solution to broken service-delivery chains isn’t to replace touchpoint management. Functional groups have important expertise, and touchpoints will continue to be invaluable sources of insight, particularly in the fast-changing digital arena. (See David Edelman’s “Branding in the Digital Age: You’re Spending Your Money in All the Wrong Places,” HBR December 2010.) Instead, companies need to embed customer journeys into their operating models in four ways: They must identify the journeys in which they need to excel, understand how they are currently performing in each, build cross-functional processes to redesign and support those journeys, and institute cultural change and continuous improvement to sustain the initiatives at scale.

Identifying Key Journeys

Defining the journeys that matter and deciding where to begin the transformation requires both top-down, judgment-driven evaluations and bottom-up, data-driven analysis, to varying degrees. We recommend pursuing these efforts in parallel whenever possible.

An executive working session, drawing on existing research, may be sufficient to identify the most significant journeys and the pain points within them—the specific service shortcomings that damage customers’ experience. That research is typically fragmented and often includes data on the customer volume in a given journey, reasons for call center complaints, and obvious gaps in performance—for example, discrepancies between promises made in marketing materials and services actually delivered.

At three companies we’ve worked with, sessions of this type directed attention to key customer journey problems. The executive team at a fixed-line telecom focused on the 50% dissatisfaction rate with the installation process; the team at a leading energy player targeted the 40% churn among customers moving houses; and executive sessions at an integrated telecom zeroed in on the more than one third of new fiber-optic customers who canceled before installation or within 90 days. In each case the executive attention led to a concerted effort to fix the targeted journey, while leadership’s “walking the talk” generated support for improvement programs and broader organizational changes. These results show how initial top-down work can identify early wins (often policy or process changes that can be implemented quickly and centrally) that set the tone for further transformation.

For companies seeking just to fix a few glaring problems in specific journeys, such top-down problem solving can be enough. But those that want to transform the overall customer experience need to simultaneously create a detailed road map for each journey, one that describes the process from start to finish, takes into account the business impact of optimizing the journey, and lays out a commonsense, feasible sequence of initiatives.

This is a bottom-up effort that starts with additional research into customers’ experiences of their journeys and which ones matter most, both to customers and to business performance. A company should draw on customer and employee surveys along with operational data across functions at each touchpoint, to assess performance and gauge how it is doing relative to the competition. Best-in-class companies use regression models to understand which journeys have the greatest impact on overall customer satisfaction and business outcomes, and then run simulations to get a picture of the potential impact of various initiatives.

Doing this research and analysis well is no small task, because it typically means acquiring new types of information and assembling it in new ways. For many companies, combining operational, marketing, and customer and competitive research data to understand journeys is a first-time undertaking, and it can be a long process—sometimes lasting several months. But the reward is well worth it, because the fact base that’s created allows management to clearly see the customer’s experience of various journeys and decide which ones to prioritize.

Understanding Current Performance

Once a company has identified its key customer journeys, it must examine each one in detail in order to understand the causes of current performance. This deep dive involves additional research, including customer and employee focus groups and call monitoring. Combined with the initial bottom-up analysis, it allows the company to map the most significant permutations of each journey as the customer experiences and would describe it, revealing the sequence of steps she is likely to take from start to finish. The mapping exercise also exposes departures from the ideal customer experience and their causes, and often reveals policy choices or company processes that unintentionally generate adverse results. For example, many companies charge for phone-based technical support, thinking that imposing a fee will steer customers to self-service options. But the consequence may be numerous callbacks or inadequate do-it-yourself fixes, both of which degrade the customer experience.

A company may get millions of calls about a product and must handle each one well. It must also address the root causes of the calls.

Consider the telecom faced with 50% initial customer dissatisfaction. Executives knew the “provisioning journey”—the process of installing fixed-line service at a customer’s home—was a priority, and as they probed new data, they began to see an ominous pattern. When they surveyed new customers about their experience from the time they ordered service through installation and activation (a journey that spanned four touchpoints), they learned that although about half were thrilled with the service, giving it an eight or a nine on a 10-point scale, the other half were incensed, giving it a one or a two.

On further investigation, the firm discovered that the installation process for unhappy customers was compromised by delays that ultimately stemmed from misaligned incentives: Back-office employees weren’t measured on or rewarded for the accuracy of order tickets and so sometimes processed them with missing or incorrect information. The company’s traditional customer-experience dashboard had missed the problem because it included no measure of end-to-end success. “Our dashboard metrics were like a watermelon,” one senior manager told us. “On the outside everything was green, but when you looked inside, it was red, red, red.”

Redesigning the Experience and Engaging the Front Line

Once a company has identified its priority journeys and gained an understanding of the problems within them, leaders must avoid the temptation to helicopter in and dictate remedies; indeed, they should refrain from any solutions (including ones from outside experts) that don’t give employees a big hand in shaping the outcome. Even if a fix appears obvious from the outside, the root causes of poor customer experience always stem from the inside, often from cross-functional disconnects. Only by getting cross-functional teams together to see problems for themselves and design solutions as a group can companies hope to make fixes that stick.

The energy company identified “moving house” as a journey it needed to get right. Executives started by gathering representatives from the various operational and commercial groups involved in that journey. The setup for the meeting was low-tech yet powerful: One wall of the conference room was devoted to posters, customer quotes, and visual depictions of what customers experienced from the time they decided to move until service was activated in their new homes.

It proved to be a breakthrough meeting. Seeing the journey represented from start to finish was powerful, because no single group had ever had visibility into—let alone accountability for—the entire experience, and therefore didn’t recognize the journey’s shortcomings. It immediately became clear that the process had evolved into something far more complex than anyone had realized; there were 19 customer interactions in all. Many of the steps involved complex handoffs between internal groups, creating multiple places where things could—and did—go wrong. But the “ahas” were not just about operational glitches: Some of the unhappy customers’ frustration arose from a lack of communication at key moments when, operationally, things were working fine—for example, when scheduling end-of-service at an old address. At other points (for instance, after starting service at a new address), customers got too much information and were confused by apparently conflicting messages.

How Journeys Pay Off

Once the team members had identified the reasons for the myriad handoffs and begun to appreciate the challenges their counterparts in other operational groups faced, they could sit down to design a new approach. They brainstormed solutions in a “war room,” launched frontline teams to pilot and improve upon ideas, and empowered the teams to take risks and experiment through trial and error. Finally, they engaged customers in the design process, to ensure that the approach developed would please them. The result: a new process that was four times as efficient, far more satisfying to customers, and much better aligned with the company’s brand promise, “We deliver.” The proportion of customers dissatisfied with the experience of moving house dropped significantly, resulting in a revenue gain of €4 million. (For an example of a typical working process, see the exhibit “Navigating a Customer Journey.”)

Navigating a Customer Journey

A leading car rental company we worked with ran a similar series of cross-functional efforts—pilots at key airport locations involving frontline teams including counter staff, car cleaners, exit gate personnel, and bus drivers. Management chose several target geographies, assigned a senior executive to each, and tasked the frontline teams with three things: mapping the customer experience and looking for fresh service ideas to improve it; getting frontline employees from each of the functions to collaborate on identifying the causes of problems and finding solutions; and coordinating activities to maximize the speed of service from the customer’s point of view.

A team in one region discovered a major bottleneck: The company frequently fell short of clean cars during peak demand. Among the remedies it suggested was installing a buzzer between the rental counter and the car lot. When the line at the counter grew long, staff members could alert workers in the lot that they would soon need more cars. By the end of the pilot, the unit’s on-site customer service scores had doubled, revenues from upselling had climbed 5%, and the cost of serving customers had dropped 10%. In addition, the marketing team—involved from day one—helped identify changes to the exit process (when customers pick up a car on the lot) that boosted upsell by broadening the choice of available vehicles.

Sustaining at Scale by Changing Mind-Sets

Of course, analyzing journeys and redesigning service processes get a company only so far. Implementing the changes across the firm is hugely important—and hugely challenging. A detailed discussion of how to scale and sustain transformation initiatives is beyond the purview of this article. However, delivering at scale on customer journeys requires two high-level changes that merit mention here: (1) modifying the organization and its processes to deliver excellent journeys, and (2) adjusting metrics and incentives to support journeys, not just touchpoints.

Organizationally, adopting a journey-centric approach allows companies to move from siloed functions and top-down innovation to cross-functional processes and empowered, bottom-up innovation. Most companies keep their functional alignments intact and add cross-functional working teams and processes to drive change. To that end, many companies we have studied set up a central change leadership team with an executive-level head to steer the design and implementation and to ensure that the organization can break away from functional biases that have historically blocked change. These roles tend not to be permanent—indeed, success ultimately involves changing company culture so much that the roles are no longer needed—but they are critical in the early years. The energy company located its change team right next to the boardroom to signal the importance of its effort. The pay TV provider promoted a functional leader and had him report directly to the CEO. Several telecoms we have worked with that elected more-permanent organizational change left the cross-functional change teams in place to ensure sustained checks and balances to the natural tensions across functions. In the most effective cases, companies design cross-functional working and accountability into their core business processes, establishing clear ownership, authority, metrics, and performance expectations that supplement the existing functional structures.

Consider how this worked at the car rental business. As efforts ramped up at the pilot locations, the CEO gave each member of his executive team responsibility for implementation across all sites in a particular geographic region, knowing that would require the executives to partner with peers in challenging new ways. The CFO, for example, might be responsible for keeping tabs on cross-functional improvements in the Philadelphia area and for taking any issues that arose, including purely operational ones, up the chain of command. And although the company had a solid playbook for its first pilot, it explicitly challenged the teams in each location to adapt the playbook and make it their own, and to try to beat the original location’s results. The frontline teams were empowered to continually test new ideas that the executives heading the teams could then spread to the rest of the business.

Back at the energy company, the scope was broadened to include five critical journeys, with an executive team member leading each effort and conducting weekly reviews with stakeholders from each function. And at the integrated telecom, the executive team created a new permanent role, redeploying senior people from siloed functions to become “chain managers” responsible for overseeing specific journeys, such as fiber cable provisioning. It created war rooms where the chain managers could monitor the efforts and meet with the functional teams involved. Thus the program was driven by cross-functional, bottom-up idea generation but had enough top-down ownership and coordination to maintain momentum and focus.

Once their new management structures are in place, organizations must identify the appropriate metrics and create the appropriate measurement systems and incentives to support an emphasis on journeys. Even if a company already uses a broad customer satisfaction metric, moving the focus from touchpoints to journeys typically requires tailored metrics for each journey that can be used to hold the relevant functions and employees accountable for the journey’s outcome. Very few companies do that today. For the telecom focused on new product installs, this meant holding the sales agent, the technician, the call center, and the back-office agents responsible for a trouble-free install and high customer satisfaction at the end of the process, instead of simply requiring a successful handoff to the next touchpoint. For the energy company, it meant new cross-functional measures for each frontline employee who handled address changes (for example, error-free capture by call center agents of information needed downstream). Disney famously builds its entire theme park culture around delivering the guest experience: From hiring through performance reviews, it assesses each frontline team member on his or her customer-friendly skills. And one large retail bank started requiring each executive-team and board member to call five dissatisfied customers a month—a simple but effective way of holding the leadership’s feet to the fire on customer experience issues.